The Zorachs

“My husband and I held joint exhibits for many years; we were a team...”

-Marguerite Zorach, Women in Art, Christian Science Monitor, April 12, 1926

If a writer were to imagine the early lives of Marguerite and Bill, their meeting and falling in love, and their early years together, it would scarcely be a plausible story. It would be hard to imagine that they both became artists, both ended up in Paris, met, fell in love despite their contrasting backgrounds, remained together through years of poverty and struggle, and ultimately both led successful careers.

Marguerite was born in Santa Rosa, California, in 1887, but grew up in Fresno, California, then a small and rough town. Her parents were WASPs with colonial roots, affluent and cultured; her father was a successful lawyer. She learned to play the piano and became fluent in French and German. She was also a talented draftsman; this interest and ability came to her naturally. After finishing high school, she taught briefly, then enrolled as a student at Stanford University. Soon after her arrival at Stanford, her Aunt Addie, Harriet Adelaide Harris, an artist who was living in Paris, contacted her and invited her to go to live with her there to study art. Her mother particularly was aghast, quite literally feeling that for a woman being an artist was just like being a prostitute. Without hesitation, however, Marguerite packed her bags again and headed off. Her aunt hoped that she would enroll in a traditional academic school, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, and she might well have done so had she not flunked the entrance exam, which involved drawing a nude from life, something she had never done before. Fortunately, too, she had visited the Salon d’Automne, a venue for avant-garde art, shortly after arriving, and was immediately smitten by the novel style of painting she encountered. Although she was fluent in French, she soon inexplicably enrolled in a school where instruction was conducted in English, that of Duncan Fergusson, a Scottish fauvist painter.

Bill, on the other hand, was born in Lithuania and was Jewish. He was a couple of years younger than Marguerite, an age difference that in that era was more significant than it would be now. His family emigrated to the United States when he was young and settled near Cleveland. They were impoverished; his father was a junk dealer. Never a consistent student, he left school after seventh grade. He had a series of brief, entry-level, brutal, dead-end jobs but finally ended up in a lithography shop. He, too, had had a passion and aptitude for drawing, and this job was pivotal. There he first learned about the difference between commercial and fine art and decided he wished to become a “real artist.” After studying in New York, he was determined to go to Europe; only after a debate did he decide to go to Paris rather than Munich. Once in Paris, since he did not understand French, he, too, enrolled in La Palette, where he met Marguerite and, finally overcoming his shyness, began a relationship with her. We do not know if their contrasting backgrounds ever made them hesitate, but, if so, their love for each other and for art seems to have easily overcome their doubts.

They planned to marry but once again her family was appalled. In order to break up the relationship, they arranged for Marguerite to travel home on a long journey eastward through the Middle East, India, Burma, and Japan, among other places. This scheme was unsuccessful; Marguerite left California for New York within a year to marry Bill. Although they were finally together, life remained a struggle for some time. They were quite poor. At that point it was even more difficult to get established as an artist than it is now; people actively disliked avant-garde art, and there were few art galleries selling it. They were involved, however, in an exciting and creative world. They held soirées in their home where they wrote poetry with the likes of William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, and Wallace Stevens. They worked with the Provincetown Players, Eugene O’Neill, and Edna St. Vincent Millay. Alfred Stieglitz took a portrait of Bill; Charles Sheeler took portraits of Bill’s sculpture. Their creative community included Louise Bryant and John Reed, Hunt Diederich, Marsden Hartley, Gaston Laichaise and Max Weber. They became associated with Edith Halpert’s newly established but now famous Downtown Gallery; Abby Aldrich Rockerfeller fell in love with Marguerite’s embroideries and became a patron of hers. As their works became known, respected and began to sell, their livelihood and careers, once endangered, began to thrive.

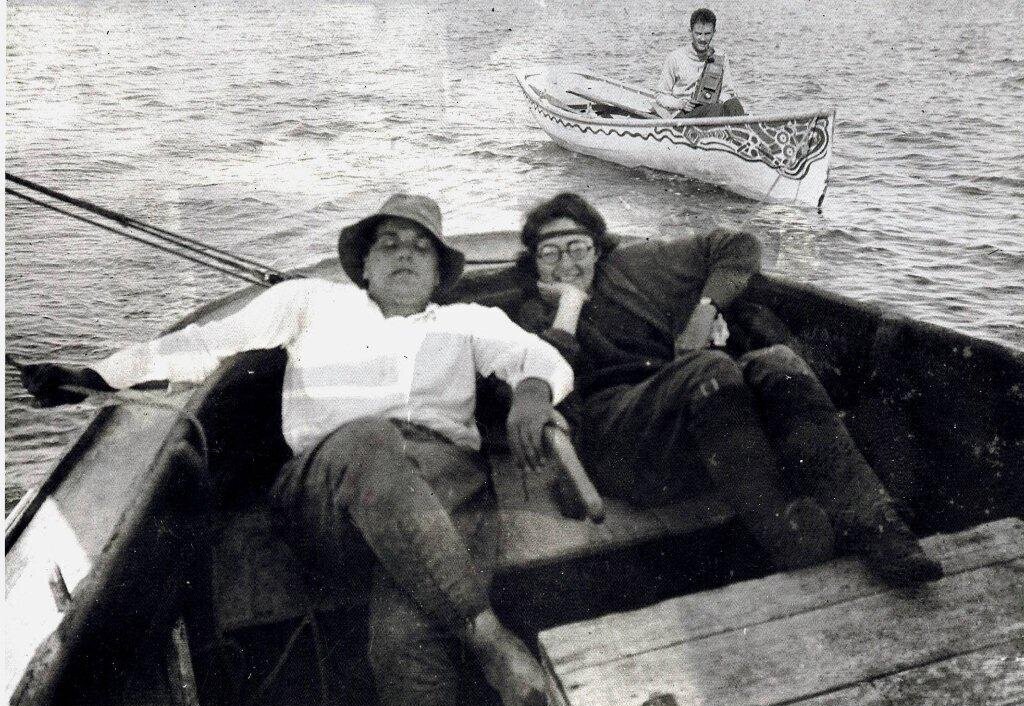

Marguerite and Bill would have a long and happy life together, one in which each supported the other’s artistic careers. Initially, when they were both oil painters and both experimenting with Fauvism and Cubism, Marguerite led the way, but they shared artistic styles as well as what their vision of what art could or should be. Later, Marguerite would continue to paint in oil and Bill would switch to watercolor and sculpture, but they both would remain modernists, each with their own vision. They shared common interests that provided them with subject matter, their love of their family, friends, and acquaintances, and also of nature. Sometimes one of them would borrow an image from the other. Marguerite would help Bill with the designs of some of his works. They were full of admiration for one another. Women at that time were not taken seriously; remember that women did not yet even vote, few women received educations, and nobody had yet conceived of an equal rights amendment. Bill would insist that Marguerite be allowed to exhibit beside him.